The Portable Confessional Unit (PCU) began with the simple premise that self-expression is the foundation of all art and that to repress that expression was unhealthy for culture and toxic to the individual. Ultimately, it had as much to do with us confessing our own secrets as it did with encouraging others to do so. There was a lot to purge and we recognized the confessional booth as a great vehicle to do it.

PDL isn’t a religious bunch, but we know a good idea when we see one. Making our own confessional wasn’t a disrespect to Catholicism; it was liberating a practice that we thought everyone could benefit from. It wasn’t about sin and repentance and forgiveness, not about heaven and hell and all of that. Our confessional booths were more like Honey Buckets - Sani-Cans for all of the thoughts you collect and process but need a place for release.

Jason built the first prototype out of a couple of bedsheets and plywood. He set it up in a corner of the Hideout and hung a sign. It looked straight out of the Little Rascals. But as comical as it appeared, what happened inside was quite serious. We spilled our guts and the audience spilled theirs right back. And amazing as it may sound, when you emerged, it felt like leaving behind a big steaming pile of repressed thought.

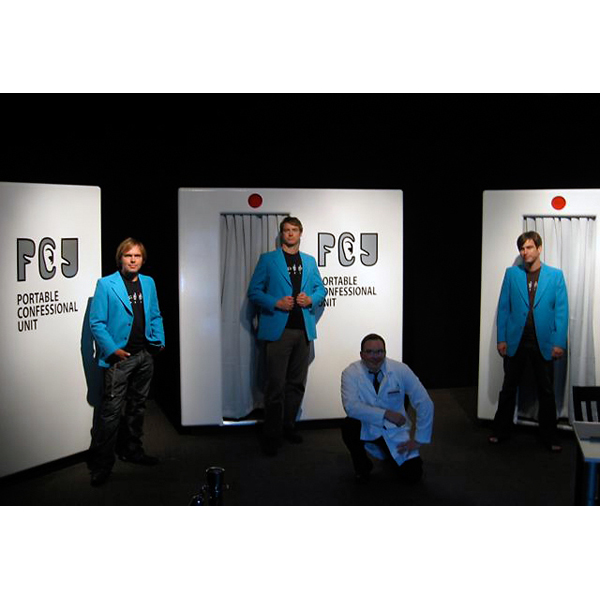

Soon enough, we were building three fancy versions of the Portable Confessional Units (PCUs) for the 2007 Bumbershoot Festival. We refined the aesthetic, put some serious energy into their construction, and even made an infomercial showing how the device worked and how great an addition it would make on college campuses and in corporate lobbies. We invented terms like Toxic Thought Syndrome (TTS) and Conversational Deprivation Disorder (CDD). But behind all of the humor, we were quite serious about these simple wood-constructed boxes, and we listened with great sincerity. And people more often than not participated quite whole-heartedly.

On August 31, 2007, we set up our three PCUs, loaded them up with water, snacks and flashlights, and crawled inside. For four days we sat in the dark confines of our units, emerging only for trips to the bathroom and short breaks to stretch our legs. We talked to hundreds and hundreds of people, from teenagers with newfound issues to parents and grandparents with longstanding problems. People who needed someone to talk to, someone to listen to them and offer comments. There were confessions of shoplifting, of infidelity; folks came clean about being totally bored with their lives, hating their bosses, wanting change; insecure adolescents fretting about not being 'normal;' a Muslim youth venting stress about his parents' strict plans for his life, and even a gay kid coming out for the first time. Most often than not, we talked back, sharing our own life experiences in similar circumstances, or relaying stories of friends' struggles, when relevant. We made no claims of being trained professionals or holding licenses or degrees to consult, but we also didn't condescend or offer any personal moral authority. We just listened, shared, comforted, reassured, told people that they were okay. It was the teenagers who were in most profound need of someone to talk to- afraid of judgment from their peers, trouble from their parents, and devoid of reliable counsellors or teachers to confide in. What we learned is that sometimes people just need someone anonymous to talk to and space to air their issues without consequence. We came away believers in the practice of confession, especially when it was devoid of a hefty professional pricetag, societal stigma, or religious shame.

The following summer, we set a PCU up at Smoke Farm, in the middle of a field, at an arts festival near Arlington, WA. We braved soaring temperatures, confined in our little poorly-ventilated boxes, giving council until the wee hours of the night, often to the surprise of festival-goers who couldn't fathom that an actual person was on the other side of the wall. Again, the results were the same.

Unfortunately, as is the case for large sculptural pieces, finding permanent homes for the PCUs became a challenge. None of us had the means to store them long term, and they all met disparate fates- one of them was transformed into a set piece for a stage show at the Triple Door before being scrapped, another became a chicken coop for a couple years in a Wallingford backyard before its demolition, and the last one, after a weekend of public service at the First Hill bar the Hideout, ended up being carted away to someone's property in Snohomish county for uncertain ends.